Prof. Xu Bin: China's economy must perform a delicate rebalancing act

The following insights are taken from a keynote speech given by Professor of Economics and Finance Xu Bin at the CEIBS Global EMBA Economic Outlook 2026 on January 17. Professor Xu diagnoses the difficulties currently facing the Chinese economy, suggesting three strategic directions for rebalancing and transforming its long-term fortunes.

A tale of two periods – Miraculous growth then a new normal

The beginning of the new millennium has seen the Chinese economy experience two broadly identifiable periods that have shaped it into its current form.

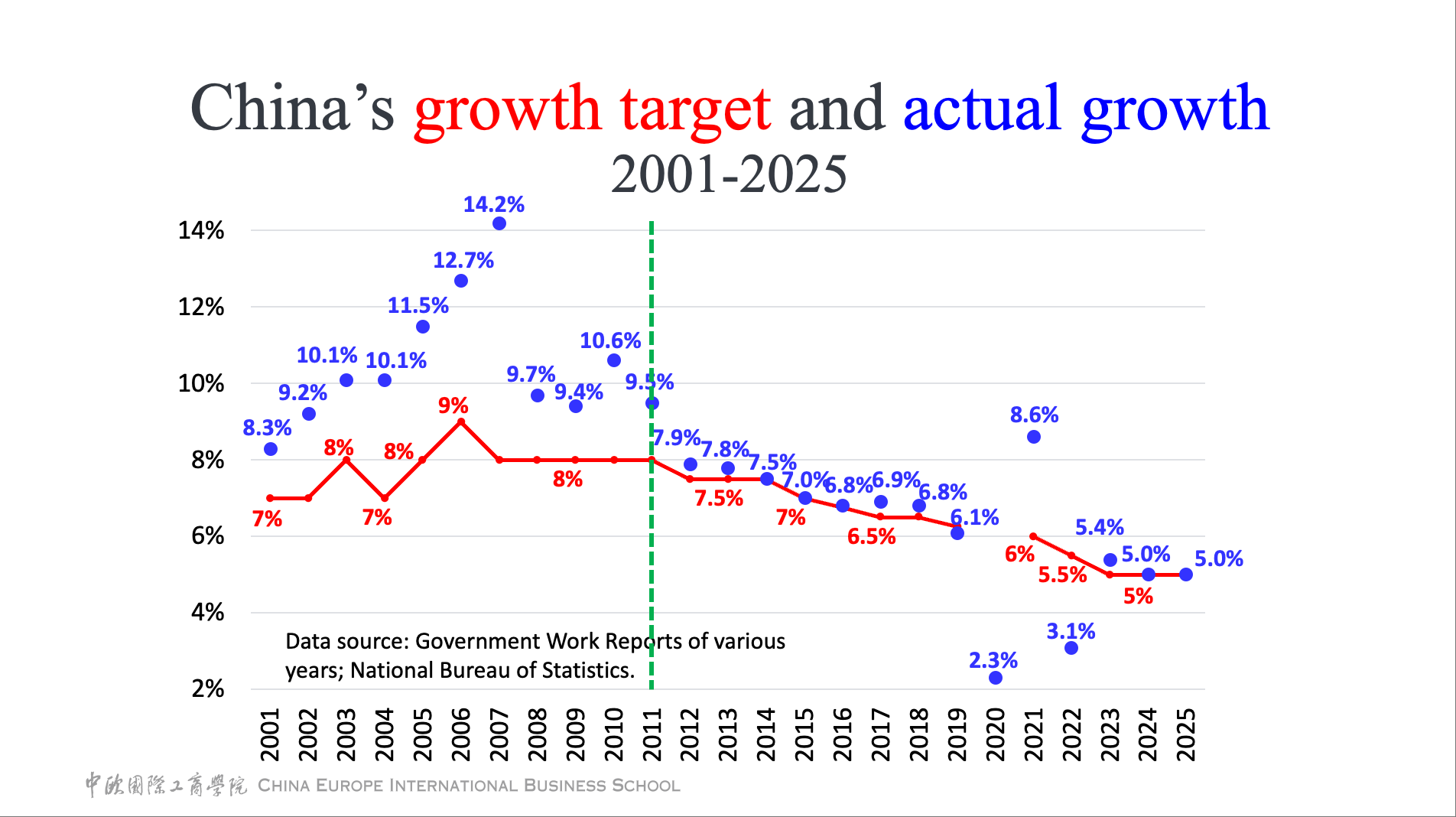

The “Miraculous Growth Period”, which spans the years 2001-2011, represented a decade where actual growth outstripped the conservative growth estimates set by the Chinese Government, without fail. Official targets of 7-9% were surpassed by several percentage points (8.3-14.2%) as the Chinese economy exploited its traditional strengths to the fullest, while taking care to develop new ones.

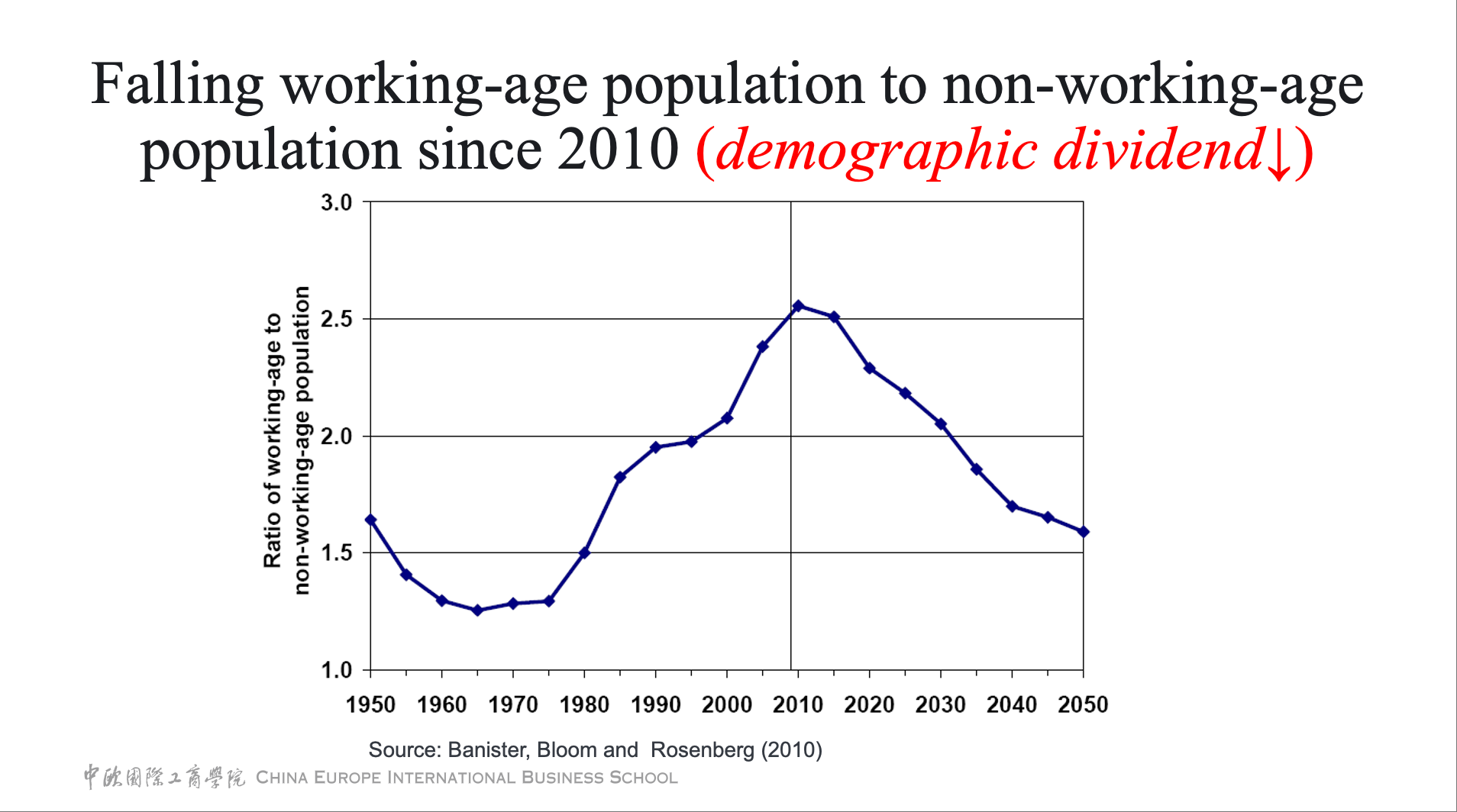

This decade saw China’s ratio of working to non-working population rise swiftly, creating a massive labour pool eager to learn new skills, engage in entrepreneurship, and create value for themselves and the wider economy. This demographic dividend, paired with strong investment and a little bit of good luck (an essential ingredient needed for any nation to excel) in the form of favourable global trade conditions explains the explosive economic growth of this decade.

However, by 2012, the boom years were over and a “New Normal Period” was firmly established. In this following decade, real GDP growth would slope downwards each year, gradually declining from 7.9% in 2012 to 4.9% averaged over the 2020-2022 pandemic period.

The “cooling off” of the previously superhot Chinese economy coincides with several seismic changes. 2008 was the high point of globalisation, and while China escaped the worst effects of the Global Economic Crisis, the world’s sharp turn towards deglobalisation has come with a dose of economic pain. China’s own demographic dividend had also reached a high point; from 2010 onwards, it consistently dropped as the Chinese population aged.

Even though China became a global production powerhouse in the 2000s and 2010s, the 2012-2022 years demonstrated that its current economic approach had delivered as much growth as it could. In fact, the nation’s TFP (Total Factor Productivity) was no longer growing, but shrinking. From 2007 to 2012, TFP fell by 2% annually, and from 2012 to 2023, TFP declined by another 1% annually.

Are we in a “new” new normal? What comes next?

As we enter 2026, what is the overall position of the Chinese economy, relative to its biggest global rivals and partners? Despite the ongoing difficulties, it still grew by 5%, outperforming practically every developed economy worldwide, and showing its resilience in a post-pandemic world.

However, those difficulties cannot be ignored if long-term growth stability is to be maintained. China’s population is shrinking, no longer delivering the economic dividend that once formed an integral engine for growth. Every year for the past four, the overall population has declined. In 2025 it shrank by 3.39 million as China’s overall fertility rate dropped to just 1 birth per woman, one of the lowest in the world.

Gross savings rates and overall investment rates are falling too – dropping 7.2 percentage points and 5.5 percentage points respectively over the past 15 years. Together, these factors reinforce the school of thought that China can no longer rely on many of its traditional sources of economic strength.

Beijing is aware of the need for an economic transformation and is eager to make it happen. Recent policy decisions and state-led investment initiatives are supportive of increasing domestic consumption and promoting emerging industries such as AI, electric vehicles, battery technologies etc. This all points towards a government-led transition from “high-volume” economic growth to “high-quality” growth.

Such a recalibration is necessary if the Chinese economy is going to develop new sources of strength that don’t merely drive growth, but also long-term resilience in an increasingly volatile world.

My personal theory is that this rebalancing act should focus on three main actions:

- Increase support for the private sector.

- Raise the share of personal income in national income.

- Build international economic relations on mutual respect and win-win cooperation.

Step 1: Private sector support means “opening the door gap”

Allowing the private sector to flourish means relinquishing some measure of control – this is the age-old dilemma that faces the Chinese Government. Rein in private business too tightly and they risk stifling its ability to innovate and drive growth; allow too much freedom, and they risk a critical loss of influence and oversight.

This dilemma has led to what I call the “Door Gap Theory”. The government carefully leaves the door open a precise amount that is designed to balance its competing needs for a private sector that is both successful and compliant to its wishes. When the economy falters, they widen the gap with supportive regulations and greater freedoms. However, when momentum builds too quickly behind private enterprise to the point where it presents a possible destabilising factor, the gap quickly narrows.

The space of the gap is not universal across the entire private sphere either; it is sector specific. In recent years, the gap has been slowly widening for the likes of renewable energy, EVs and AI, while it has almost swung entirely shut for real estate, as the state steps in to reassert control and limit the damage being done.

Widening the gap is essential for the kind of industrial modernisation that will fuel China’s economic transformation. Fast-paced innovation can be more readily achieved if the private sector is given greater flexibility to raise capital, pursue strategic partnerships and adopt new practices and technologies, all without having to work around overly proscriptive regulations.

Step 2: Put more money in Chinese people’s pockets

While China continues to develop strong export ratios and manufacturing capabilities, being a “factory for the world” is not enough to guarantee sustainable economic growth. Without developing markets at home, China remains vulnerable to global shocks that compromise its overseas customers’ ability to buy at scale.

Even though the “Dual Circulation Strategy” was launched back in 2020, China’s domestic consumption remains weak. Retail sales growth in 2025 was marginal, while property investment dropped 17.2% for the year. In the face of growing economic challenges, Chinese people are spending less, and saving what they can.

Boosting Chinese domestic consumption meaningfully will require the Chinese Government to actively put more money in people’s pockets. Like the dilemma outlined in the Door Gap Theory, this is another trade-off between encouraging growth and maintaining direct control.

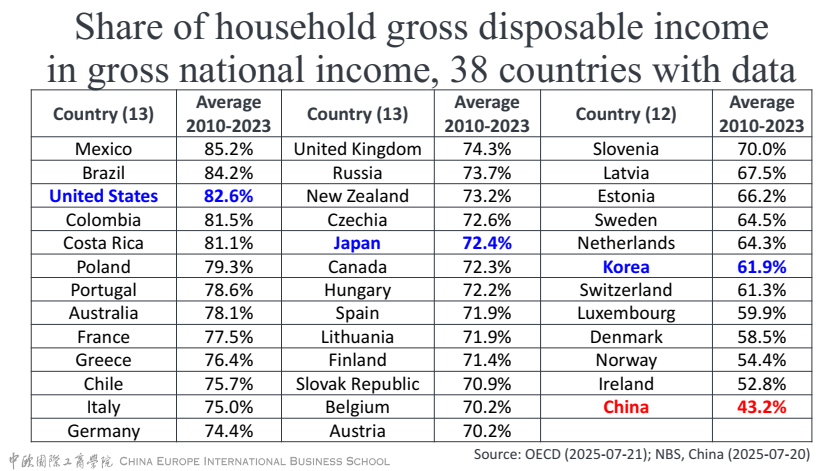

Currently, Chinese households have among the lowest share gross disposable income in the world, compared to gross national income. For every 100 RMB created, only 43.2 ends up in the hands of Chinese consumers, with the other 56.8 remaining within the public purse. If the government wants people to go out and spend more, then this ratio must be rebalanced to give them the financial security and general confidence to make more discretionary purchases.

That means, simply put, letting them keep more of the money they earn.

Step 3: Promote greater international cooperation

China’s problems at home – weak domestic demand and a growing housing crisis – only serve to underline the importance of maintaining strategic partnerships and even genuine friendships abroad.

China is now more actively pursuing “soft power” and cultivating its image as a more responsible global leader. These ambitions are not separate from China’s economic growth aims; they are interlinked. By creating more stable, cooperative relations with other nations, China broadens its opportunities to forge stronger trade links and gain access to those technologies and resources that it does not already control.

In an uncertain world, smaller nations seek friendships with larger ones. 2026 has already proven how uncertain and unpredictable the global political landscape has become. In January alone, the Trump Administration has dramatically intervened in Venezuela, vowed to take Greenland (a territory of its NATO ally Denmark) by any means, and threatened a new round of 10-25% tariffs on its European partners.

In its second term, the Trump Administration seems increasingly determined to pursue “The Donroe Doctrine” – a modern-day version of the Monroe Doctrine – to assert US predominance across the Western Hemisphere. Its willingness to use threats and overt military force is driving a wedge between the US and its closest allies.

At a time of such instability, China should play a stronger global leadership role characterised by respect, restraint and responsibility. The aim is not to replace the United States, but to offer an alternate path by acting as a stabilising force for global institutions, the international rule of law, and, consequently, global enterprise.

Stability, progress, transformation

With Chinese economic growth bottoming out (though 5% remains the envy of most developed economies), stability is currently the primary policy objective. “Fixing” the housing crash through tighter controls while boosting emerging tech sectors will be the likely path ahead, while aggressive macroeconomic stimulus policies are unlikely at this point.

However, the government has demonstrated its understanding that the private sector will have to play a more significant role in boosting economic growth, and that means giving emerging tech-related industries a wider door gap in which to thrive. Equally, the government will likely pull some appropriate tax levers to give the average Chinese consumer more financial space to breathe, and consequently, spend.

Looking beyond the short-term, slow yet steady progress is the most likely prospect. Even if dazzling technological breakthroughs remain possible, we should expect both the supply and demand sides to transform at a steady pace, as the government and state-led institutions seek to carefully rebalance the economy for a new period of sustainable growth.

Xu Bin is Professor of Economics and Finance, Wu Jinglian Chair Professor in Economics at CEIBS. His current research focuses on the global and Chinese economy, multinational enterprises in China, and trade and finance Issues of emerging markets.